Shaping the landscape with fire and iceShaping the landscape with fire and ice

In the weekly Museum Musings column in Pique Newsmagazine, we mostly explore and share stories of the past. Rarely, however, do we go back thousands or millions of years as is required when talking about the geological history of our region. In celebration of the Sea to Sky Fire and Ice Aspiring GeoRegion, the Museum is showcasing the landscape in the new exhibition Shaping the Landscape with Fire & Ice.

Throughout time, fire and ice have played an important part in shaping the land. Whistler sits in the subduction zone of converging tectonic plates, where the Juan De Fuca plate is being pushed under the North American plate, creating the Coast Mountains. All of the volcanoes considered active in Canada are found in BC and the Yukon along tectonic plate boundaries, and all are part of the Pacific Ring of Fire.

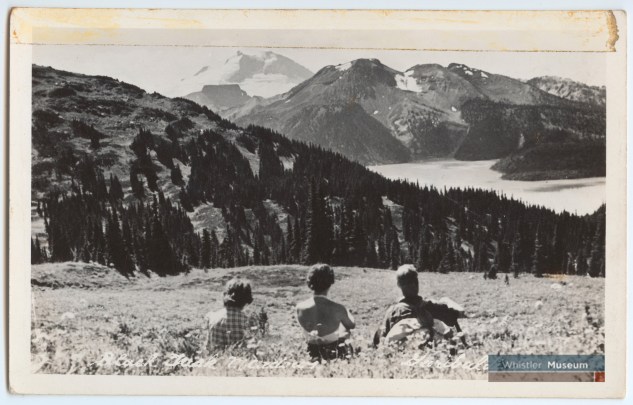

Garibaldi Provincial Park is named after Mount Garibaldi, the largest mountain in the park and a potentially active stratovolcano. While the last eruption was around 13,000 years ago, this is still relatively recent in geological time (Black Tusk, on the other hand, likely erupted approximately 170,000 years ago). Volcanoes can erupt again after being dormant for thousands of years. Thankfully, if Mount Garibaldi was to rumble back life to we would start seeing warnings such as hot springs, hot spots and seismic activity in the region from rising magma.

While Mount Baker is instantly recognisable as a volcano, Mount Garibaldi is harder to distinguish because it is not a typical cone shaped volcano. When Mount Garibaldi erupted during the last ice age, one half of the volcanic cone formed on a rock foundation, while the west side settled on top of a glacier. As the glacier melted and receded the mountain collapsed, changing shape. Giant landslides spread the volcanic debris across the Squamish Valley.

We can thank this active volcanic region for the formation of Garibaldi Lake. Also around the end of the last glaciation, Clinker Peak on the shoulder of Mount Price erupted. The Cheakamus Valley had been full of ice over 1.3 km above sea level that was rapidly melting. Lava from the Clinker Peak eruption flowed towards the valley below where it hit the Cheakamus Valley glacier. There it cooled rapidly against the wall of ice, solidifying to create a dam across the mountain valley. As snow and ice melted from the mountains above it became trapped behind this wall, known as The Barrier, creating Garibaldi Lake.

The only water that leaves Garibaldi Lake year round gushes from springs coming through the scree slope below The Barrier. This consistent flow of water lubricates the bottom of the naturally unstable dam and poses a significant geological hazard, with some scientists worried it could one day collapse. It is not uncommon to see rocks fall from The Barrier, hence the name of Rubble Creek below, and according to indigenous oral histories a major landslide occurred 1855 when a slab of rock fell from The Barrier. With approximately 1.28 trillion litres of water trapped by an unstable dam wall at 1400 metres of elevation, a collapse could be catastrophic. It is for this reason that an evacuation order of Garibaldi Townsite was issued in 1980, with the last residents leaving the town in 1986. Today the Garibaldi Townsite no longer exists.

Shaping the Landscape with Fire & Ice is on now at the Whistler Museum, open from 11am every day except Wednesday. Entry is by donation, and you can further support the Whistler Museum by becoming a Museum Member.