Charlie Chandler and the Runaway BannockCharlie Chandler and the Runaway Bannock

This week, we thought we’d take a look at the life and legacy of Charles Ernest Chandler, one of Whistler’s earliest European settlers. Locally known as Charlie, he was a trapper during the beginning of the twentieth century. He came to the Whistler valley from Wisconsin in 1908 to pre-empt about 160 acres on the northern end of Alta Lake.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with the term, pre-emption was a method of acquiring Crown Land from the government for agriculture or settlement. It was formally established by the Land Ordinance in 1870, and was still legal until 1970. In order to pre-empt land, a person (the pre-emptor) would have to stake out a block of unsurveyed, non-reserved Crown Land and submit an application to the government. If their application was approved, the pre-emptor would receive a Certificate of Pre-emption, and they would be free to begin “improvements.” After appropriate development had taken place, the pre-emptor would receive a Certificate of Improvement from the government, which would allow them either to buy the land at a discounted price, or receive the title for it outright. Pre-emption often did not take into account indigenous claims to land, and the land that was pre-empted by Chandler was part of the unceded territory of the Squamish and Lil’wat Nations.

For the next three or four years, Chandler spent his time improving the area he had pre-empted in order to gain title for it. His move to the Whistler valley was meant to give him a fresh start, away from the influences of “the bottle.” According to Dick Fairhurst, Chandler though the best method to solve such a problem was “to get the hell away – out in the woods, some place it [alcohol] wouldn’t be too handy.”

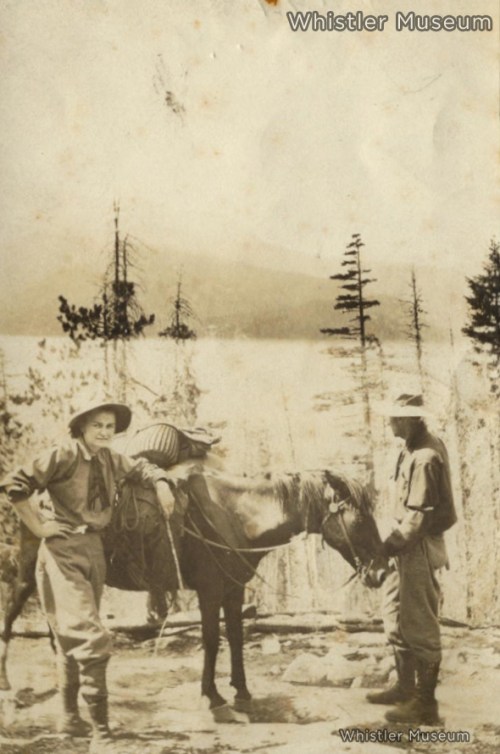

He also spent his time working on his trap lines, which ran along Wedge Creek all the way to Wedge Pass, and about 1.5 km down Billy Goat Creek on the Lillooet divide. He occasionally made money taking people on hunting trips along his trap lines, as well, which is how one of his many colourful stories came about.

One night, while guiding Alex Philip on a hunting trip, Chandler was cooking his typical fare of bannock for dinner. The camp they had pitched sat at the top of a steep slope, and when Chandler tried to flip the bannock over in his frying pan, he missed. The unfortunate bannock flew out of the pan and went cartwheeling down the ridge. Chandler, the determined man that he was, went chasing after it. The bannock put up a bit of a fight, it seems, but eventually, with a well-placed stomp, Chandler caught his dinner. By the time he made it back up to the camp, the bannock looked more than a little worse for wear. Chandler, however, just looked at the messy ball of dough and said, “You look a little dirty, but we’re eating you anyway.”

Chandler sold ten acres of land to Alex and Myrtle Philip in 1913, which they would quickly turn into the famed Rainbow Lodge property. Chandler himself moved further north along Alta Lake to settle in the area now known as Alpine Meadows. He built his homestead there, where he lived until passing away peacefully on his porch in the winter of 1946.